Lifetime experiences

There is huge potential for reducing suffering and improving welfare by thinking carefully about how every event might be experienced by the animal and how each one can be optimally refined.

Sourcing

-

Animals may find it stressful to be placed in a breeding pair with an unfamiliar animal. Some techniques associated with breeding, creation or maintenance can cause pain or discomfort, e.g. injections to promote superovulation in mice. Young animals and dams of many species, including rodents, may experience distress when separated from each other. If surplus to requirements (e.g. due to age, sex, weight, undesired genotype, uneven demand), animals may be killed – which can cause suffering (see ‘Humane Killing’).

Examples of actions: Review practices to avoid or refine invasive techniques, and colony management to minimise ‘wastage’ or overbreeding; try to avoid early maternal separation.

-

Animals will likely experience fear and distress from being trapped and confined. They may find being restrained and handled by humans – who they may perceive as predators – a stressful experience. They will be exposed to unfamiliar smells and noises and will be unable to remove themselves or ‘escape’ from the stressful situation.

Examples of actions: Review and refine trap design and carefully consider when and where traps are placed. Ensure equipment is well maintained (e.g. to minimise potential for animals to injure themselves) and check traps regularly to minimise the period animals are confined. Act calmly and quietly around animals.

-

Animals may find it disorientating to be taken from their home cage and placed, maybe with unfamiliar individuals, into a confined container. They will likely be distressed if they experience vibrations, a wider range of temperatures, noise and new smells, e.g. whilst in a vehicle or airplane. They will be met by unfamiliar animal care staff.

Examples of actions: Where possible, send eggs, sperm or embryos; minimise journey duration, noise and vibration; review reception, quarantine and health screening protocols. Plan and liaise with colleagues to minimise moving animals within the animal house unless this is for essential scientific or animal welfare reasons, e.g. to an exercise area.

Housing, husbandry and care

-

Being caught and restrained is likely to be stressful. Identification techniques that involve puncturing the skin, or removing tissue, will be painful.

Examples of actions: Use non- or minimally invasive methods, including using natural coat markings, or skin patterns, e.g. for Xenopus frogs. Consider whether the same procedure, e.g. ear punching in mice, can be used for both identification and genotyping (see ‘Genotyping’). Use local anaesthetic and/or topical analgesia where appropriate.

-

Being caught and restrained is likely to be stressful. Biopsy will be painful. Swabbing could also cause some discomfort and stress.

Examples of actions: Ensure the minimum amount of tissue is taken; use tissue from identification procedures, e.g. ear notching, wherever possible; provide the animal with local anaesthetic and/or topical analgesia where appropriate; review the potential for non-invasive techniques e.g. faecal samples.

-

Animals spend most of the time in their home cage or pen, with little control or choice over their environment, which can cause stress. Animals may become frustrated by the inability to exercise (the space provision is a fraction of their natural home range) and bored by not being able to forage for, or consume, a variety of different foods. Animals may also find it stressful to be housed with unfamiliar animals or in inappropriate groupings.

Examples of actions: Think about the physical, psychological and behavioural needs of animals and how well these are met. Consider how you can provide animals with more choice (e.g. through enrichment, spatial complexity, diet, etc.) and opportunities for them to modify their environment, such as providing mice with materials they can manipulate to create better nests. Carefully form and manage social groups and try to keep them stable. Consider adaptations for animals with specific requirements, such as nude mice or aged animals. Review parameters such as light cycles and intensity, temperature and humidity.

-

Events such as cage cleaning, and feeding, are essential for health and welfare. But they can also cause anxiety and stress, e.g. by moving mice into clean cages with none of their scent markings, or involving noisy and disturbing practices such as filling food hoppers and cleaning the holding rooms.

Examples of actions: Ensure full cage changes are done at appropriate intervals and refined to reduce stress. Minimise noise and other disturbances in the animal facility that animals find aversive, e.g. ultrasound for mice. Think about the timing of noisy practices and how this fits with circadian patterns, lighting regimes and scientific procedures. Consider what food is provided, how it is presented to the animals, and how they might interact with it, e.g. will manipulating it ready for consumption provide physical or mental stimulation?

-

Being caught and restrained can be frightening for any laboratory animal, especially small, ‘prey’ species. Mice, for example, will not habituate to aversive handling methods such as being picked up by the tail.

Examples of actions: Remember that humans will be perceived as ‘predators’ by many species. Use methods which minimise stress or anxiety, e.g. pick up mice using tunnels or cupped hands. Use positive reinforcement training wherever possible – many species, including rodents, can learn to come to the handler and habituate to procedures such as blood sampling or oral gavage.

Scientific procedures

-

Scientific procedures can cause animals to experience negative states including discomfort, pain, nausea, anxiety, fear and distress. Each procedure will have specific adverse effects, which should be regularly reviewed with the aim of better understanding and reducing the impact on the animals used. This should be done at the planning stage, and also at stages throughout the project.

Examples of actions: Carefully go through the protocol descriptions with colleagues, including animal technologists and care staff, considering everything that will happen to the animal. Try to think about and predict how the animal might experience each event – will it hurt? Might the animal feel frustrated or afraid? Make sure the cause(s) of each potentially negative experience have been fully refined, seeking expert advice from colleagues and your local ethics committee or equivalent body.

-

Following a procedure, an animal may for example experience pain, nausea or anxiety. They may also be in discomfort as they try to move around, or eat or drink. As many species used in laboratories are ‘prey’ species, they may hide feelings of pain or vulnerability.

Examples of actions: Ensure people using or caring for animals have a thorough understanding of the natural behaviour of the study species. Create a welfare assessment system that is tailored to the study, including indicators of expected adverse effects, humane endpoints and other observations, and ensure that staff monitoring animals are trained to use this. Some animals may need help getting to food, or eating (for example, rats may benefit from wet mash or jelly on the floor of the cage), or rodents will find comfort from being provided with additional nesting material to help them feel safe and maintain their body temperature whilst they recover.

After procedures

-

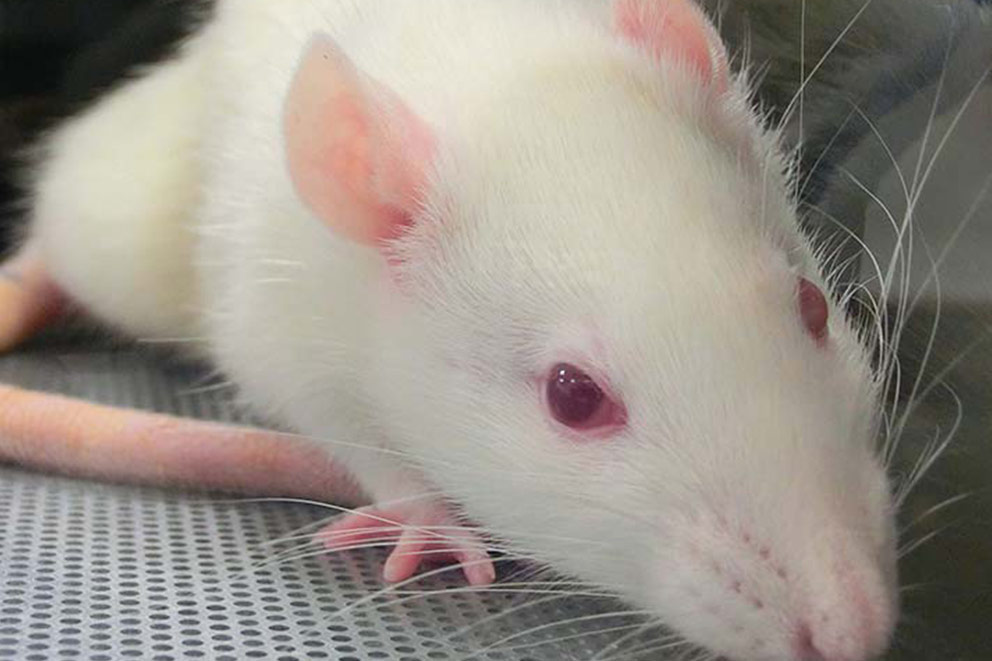

Humane killing techniques usually involve capture, restraint and administering substances, which can cause anxiety, distress and discomfort or pain. For example, mice and rats find carbon dioxide unpleasant and are frightened if they are not able to escape from the source. They will also experience stress if they are moved away from their home cage for the humane killing procedure.

Examples of actions: Question whether it is essential to kill the animal for scientific or animal welfare reasons, or could they be rehomed (see ‘Rehoming or release’)? Even if a humane killing technique is on an approved list (e.g. Schedule 1 in the UK or Annex IV in the EU), always question whether it is the most appropriate and fully refined process. Could animals be killed in their home cage to reduce stress?

-

All animals have intrinsic value as individuals and some may be rehomed or released to the wild if it is in their best interests. However, it should be kept in mind that any change in living environments can cause short-term anxiety and stress, which will need to be managed.

Examples of actions: Have in place a carefully developed plan, which ensures animals are optimally physically and mentally prepared to be rehomed or released, with appropriate monitoring and follow up as far as possible. Ask your local ethics committee, Animal Welfare Body/AWERB/IACUC, for advice.